Semiotics and Semaphores: A History of the Polka-Dot

The Polka-Dot was inspired by the musical notation used by composers of polkas to create a staccato effect which mimicked the newly invented telegraph.

Semiotics is the study of signs and symbols, and a semaphore is using a device, like a flag, for purposes of signaling over distances. It is with these definitions that we can begin the history of the polka-dot in the 19th century.

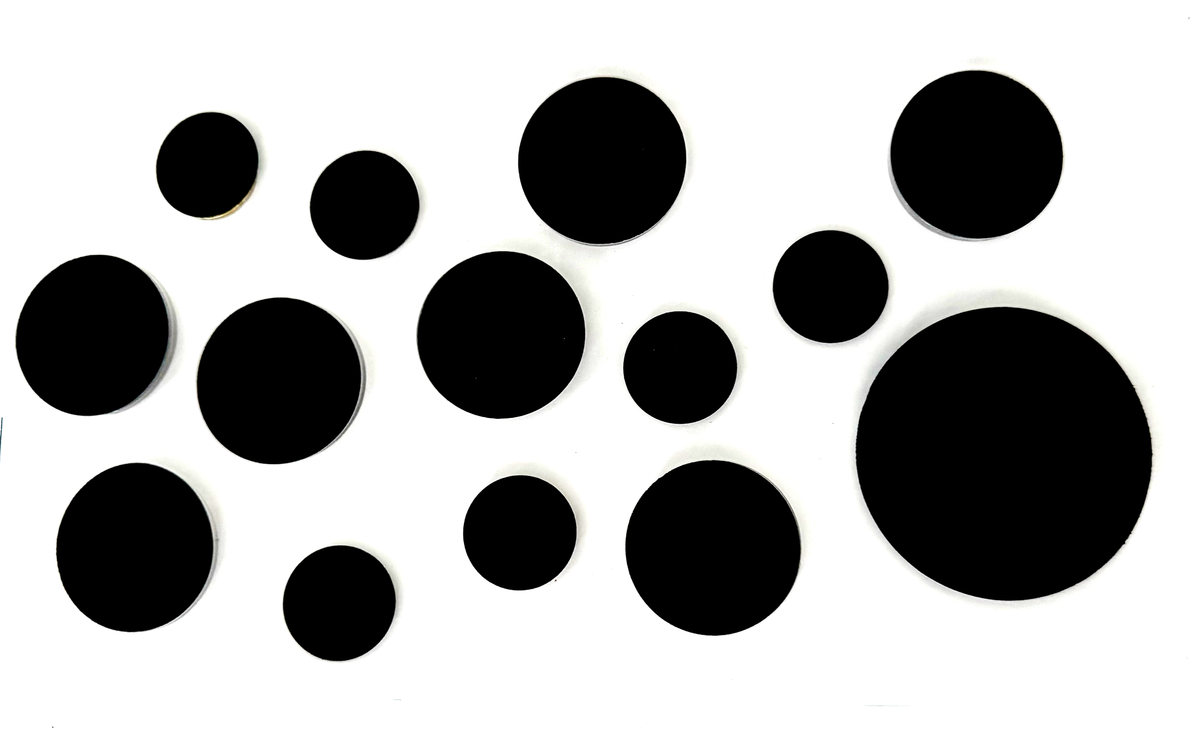

Sometime during the 1850s people began to use the phrase "polka-dot". It seems that ever since its inception, that phrase was associated with a sort of dotted pattern. The design has gone in and out of fashion, naturally evolving like every other trend. In its earliest iterations, the pattern would have been somewhat orderly, featuring dots of the same size and color, and a regular spacing schema. Over the next century, the polka-dot became chaotic, with the dot size, color, and spacing all becoming arbitrary. It would become common on bow-ties and bathing suits alike.

The use of polka-dots would become associated with quirkiness. Yayoi Kusama, the Japanese artist, uses polka-dots in (nearly) all of her art. If a writer mentions that a subject is wearing a polka-dot bowtie or socks, you can be sure that he is being depicted as the opposite of staid.

The Polka-Dot as a Symbol

The question is, how did the polka-dot come to be?

Conventional Wisdom

The usual litany of dictionaries, encyclopedias, and other sources assumes that the polka-dot is named after the polka because of the popularity of both during the second half of the 19th century.

After much research, I can say with near certainty that it was not because of a dotted polka fabric, whatever that may have been. The story is so much more interesting, in my opinion.

Polkamania

Around 1840, a new music style and dance came from Bohemia to Paris, France. The name became Polka, as a tip of the hat to its roots, as the word Czech word půlka meant "half", and the time signature of the Polka was 2/4, as opposed to the 3/4 of the Waltz.

While the dance had nothing to do with Poland, that didn't stop people from changing anything that may have been referred to as "Polish" to "Polka". Even today, Polish-Americans celebrate the Polka, but it is not really the same dance that spurred the "Polkamania" of the mid-1800s in Europe and America.

The sped-up time signature made it a faster song and dance, and it was less complicated to learn to dance, compared to the Waltz. But the Polka even evolved in its first few decades, from being defined solely by its 2/4 time signature, to being associated by its overuse of the polka-dot.

The waltz evolved as well, with the Valse à deux temps (the Two-Time waltz) which is a faster version of the dance which was inspired by the polka.

The "Polka-Dot"

In musical notation, a dot above a note indicates to the musicians to play that note on its own, so a series of dots above notes would indicate that the phrase be played in a staccato manner.

Between the increased tempo of the music and the staccato notes, it would mimic another invention that was very popular in the 1840s, the telegraph, and specifically Morse code.

Invented by artist and anti-Abolitionist Northerner Samuel Morse in 1837, the eponoymous code had translated all letters into a series of dots and/or dashes. One of the first public tests of Morse code and his associated telegraph was announcing the nomination of slave-owner James Polk in 1844 in his bid for president. Polk's presidency was the first which would feature rapid telecommunications.

In 1837, Morse was not the only one who was trying to use dots to encode data in an simplified way. The same year in France, Louis Braille was inventing his eponymous alphabet for the blind. (Also in 1837, the first known electric locomotive was designed by the Scottish chemist Robert Davidson.)

Johann Strauss II was one of the early proponents of the polka-dot in his Polkas.

As the Polka and the telegraph both became more popular, composers began to use the "polka-dot" to mimic the dots of the telegraph. There would also be references to use of the "dash", which would be a section played without the staccato effect.

One explicit example of this is by Camille Schubert (the nom de plume of Camille Prilipp), with his Télégramme-Polka, Op.324, circa 1866.

While every Polka was defined by its time signature, the "polka-dot" would even be used in waltzes to the same effect. In 1873, the "Polka-dot" Waltz by Edward A. Abell was an example of this, by using excessive polka-dot notation in 3/4 time signature.

In an article about the 1883 Vienna Electric Exhibition, we see the playful intersection of the two.

ONE OF THE NOVELTIES at the Vienna Electric Exhibition is the electrical ballet. The chief features of the entertainment are the introduction of electro-magnets, dynamo machines, telegraph apparatus, and telephones, which were dragged on the stage by fantastic goblins, and handled by the graceful danseuses with as much ease as if they were especially trained in the mysterics of electricity, One of the prettiest scenes is the telegraph-polka, which is danced by two ladies in the costume of telegraph boys.

The Polka-Dot as a Semaphore

A lot of things were going on with clothing and fashion during the mid-19th century. Europe was beginning to dye their own clothing, and clothing was becoming more massed-produced. The machines of Industrial Revolution enabled the quick embroidery of dots.

Dots (or spots as they liked to call them) did not play into fashion before this. While we know that they must have had dotted fabrics, it wasn't what anyone would necessarily wear to be fashionable.

Additionally, there were new fabrics and styles.

And, in conclusion, we will merely further record that, among the novelties at our magazins des modes, we have an étoffe, called Polka, as pliant and graceful in its folds as the dance from which it has borrowed its name.

– Eugène Coulon, "How to dance the Polka!" (1845)

While you see references to this fabric during the mid-19th century, I'm not sure if "graceful" would have ever been a word to describe the polka dance. It was more Bacchanalian in nature, according to many.

...it is the Berserker gladness in the dance. Supported upon the arm of the woman, the man throws himself high in the air; then catches her in his arms, and swings round with her in wild circles; then they separate, then they unite again, and whirl again round, as it were in superabundance of life and delight. The measure is determined, bold, and full of life. It is a dance intoxication, in which people for the moment release themselves from every care, every burden, and oppression of existence.

– Littell's Living Age (1844)

At the beginning of my research, I spent a lot of time trying to figure out if the fabric originally had a similar name, or a name connected to the word "Polish" or to a homophone to Polka, and, truthfully, I have no idea. Similarly, I'm not sure sure if the first references of dotted polka fabric were simply the intersection of a pattern (dotted) and fabric (Polka).

That said, I came to discover what I wrote above, that the polka-dot was not just a lucky coincidence, and the idea preceded the shifting popularity of wearing dots.

In Howe's Ball-room Hand Book, published in Boston in 1858, the author provides the proper dress for a gentleman at the dance.

BALL DRESS FOR GENTLEMEN, Is invariably, black superfine dress coat, pair of well fitting pants of the sume color, white vest, black or white cravat, tie or stock, pair patent leather boots, low heels, pair white kid gloves, white linen cambric handkerchief slightly perfumed, the hair well dressed, without its being too much curled; the whole should be in perfect keeping with the general appearance, and remarkable for its elegance and good taste.

While I'm unsure if this is descriptive (how it was) or prescriptive (how it ought to be), but I do know that 7 years earlier, the London-based journal about "Music, the Drama, Literature, Fine Arts, Foreign Entelligence, &c." featured an unsigned editorial about color and polka:

We should be glad to see a taste for artistic dancing becoming prevalent in society; more life and colour infused into our rather prosaic amusements; and our ball-room crowds (at present a sort of anarchy ) grouped and organised in the performance of choregraphic evolutions having a dramatic interest. In the meantime there is more yet to be made of the Polka.

Why should not some innovator, bolder than the rest, raise the question of dress ? Why should not the eye and the artistic sense be entertained with novel and characteristic costume, as well as diversified and graceful movement ?

– The Musical World (1851)

Handkerchiefs

Handkerchiefs were likely one of the first polka-dotted items to come into vogue. They would be placed in a pocket or around a neck (usually for men), or as a head scarf or bandana of some sort (for women). It was also used for pyjamas.

In 1880, Johann Strauss Jr. had written an operetta called Das Spitzentuch der Königin (the Queen's Lace Handkerchief), which is about a 16th century Portuguese queen who fell in love with Cervantes' writing and sent him her handkerchief. While the story is fallacious, it does indicate that the place of the handkerchief in the contemporaneous social intercourse.

In his 1887 book, a Edgar "Bill" Nye writes about a 22 year old blase young man he met, and lists a rather humorous inventory of his luggage, including, but not limited to:

- 31 Assorted Neckties.

- 17 Collars.

- 1 Shirt.

- 1 Pencil to pencil Moustache at night.

- 1 Pair Tweezers for encouraging Moustache to come out to breakfast.

- 1 Polka-dot Handkerchief to pin in side pocket, but not for nose.

- 1 Plain Handkerchief for nose.

By 1888, flirting with handkerchiefs was so commonplace, there were be advertisements highlighting better ways to do it.

Semaphoric Hanky-Panky

Going by names of polka songs alone, the Hanky-panky Polka by George Maywood in 1871, and the Hanky Panky by Charles Coote, Jr. in 1885, are both great examples. In 1911, a musical with the same name was written by Alfred Baldwin Sloane, and performed in NYC to packed houses.

The phrase "hanky-panky" had a general meaning of "trickery" and was earliest associated with magic. While handkerchiefs were used in magic acts, and polka-dots were an example of that, it seems that handkerchiefs may have also associated more levels of meaning during the polka, whether in parlor games played, or on some level of social interaction that I've still been unable to discover.

For example, in Cellarius' "Drawing Room Dances", published in 1847, there is a game called "The Handkerchief / Le Mouchoir" with the following explanation:

The Handkerchief-Le Monchorè. (Waltze, polka, mazurka.) The first couple sets out. After the waltze or promenade, the lady makes a knot in one of the four corners of a handkerchief, which she presents to four gentlemen. He who hits upon the knot waltzes or dances with her to her place.

(It should be noted that in the French version, they omitted the mazurka.)

A decade later, in Howe's "Ball-room Hand Book", he describes a different sort of game.

The Handkerchief Chase — La Chasse qui Mouchoirs. (Waltz, polka, or mazurka step.) The three or four first couples start together. The gentlemen leave in the middle of the room their ladies, who should each have a handkerchief in her hand. The gentlemen of the cotillon form a circle about them, with their backs turned. The ladies toss their handkerchiefs into the air, and waltz or dance with such of the gentlemen as have the good luck to catch them.

Atomic Pointillism

I would be remiss if I didn't point out a few other dots of the 19th century:

- The 1880s technique of painting dots described by critics as "pointillism" practiced by Georges Seurat, Paul Signac, and Henri-Edmond Cross, among others.

- The electron was theorized and discovered during the same period as "Polkamania". I only mention this because the above-cited 1844 quote from Littel's Living Age "then catches her in his arms, and swings round with her in wild circles" had me thinking about electrons circling an atom's nucleus.

- While dominos (the little tiles with dots) were not invented during this period, they became more popular with the invention of synthetic materials in the 1860s. By 1889, their popularity had spread internationally. Also, the mask most commonly worn at masquerade balls at the start of Polkamania were called "dominos".