Panic! in the Garden

This month on Colorphilia, each week, we will be focusing on a different aspect of tulips. This week, I share the likely original meaning of the flower, and how the etymology became so tortured, convoluted, and misunderstood.

Roses are red, and violets are purple,

lilies are white, and tulips have no place in such a poem.

When talking about color, the tulip is a flower unlike most others. The tulip did not have such a limited, monolithic, traditional relationship with color.

By the 17th century, contemporaneous writers described the endless colors of tulips. If anything, the amount of tulip colors was compared to the sand in the sea, something uncountable.

Next week, we'll see more about the 17th century and their obsession with the many colors of tulips.

But first, why is it called a tulip?

Spoiler alert: It has nothing to do with the word turban, or even the country Türkiye.

By the end of this newsletter, you will not only understand the correct etymology, but you will also see how and why it was misunderstood, and how it can all be traced back to a 20-something year old German medical school student in 16th century Italy, who liked to draw flowers on his days off.

As you scroll through the linguistic hoops that some dictionaries jump through to connect the word "tulip" to "turban", I hope you will agree that in this case, the simplest reading is probably the correct one.

What's in a name?

We usually expect for a name to tell us something about the flower.

There are two dominant words for the flower around the world. In most languages with a Latin script, the word is some form of tulip, and we are going to figure out what that means.

In languages which use the Arabic abjad writing system, the base word is from the Persian lâle, which is connected to the color lâl (red). (Besides, Arabic itself, which may, at times, refer to it as a tulib as well.)

Outliers

Two interesting outliers are Hebrew, which simply refers to them as צבעוני or “colored”, and Basque which refers to them as idi bihotz or “ox-hearts”. What makes these both interesting is that they focus on two different of the unique identifiers of the flower.

Most Likely Etymological Origin

The likely etymology is simple and straightforward.

Tulip was originally Tulipan in Latin.

Tulipan can be split into two words: “tulī” (I have supported) and “Pan” (the god of joy and merriment).

The god Pan was half-man / half-goat, and was also associated with fertility and the season of spring, among other things.

For the record, tulī (the first-person singular perfect active indicative form of ferō) could mean I've worshipped, I've loved, I've supported, I've carried, I've borne, as well as a bunch of other similar meanings.

Pan could also mean "everything". Tulipan could also very well mean, "I've contained all [colors]." It's much more likely that it is a Pan pun, but I wanted to throw that out there.

The Mythical Family

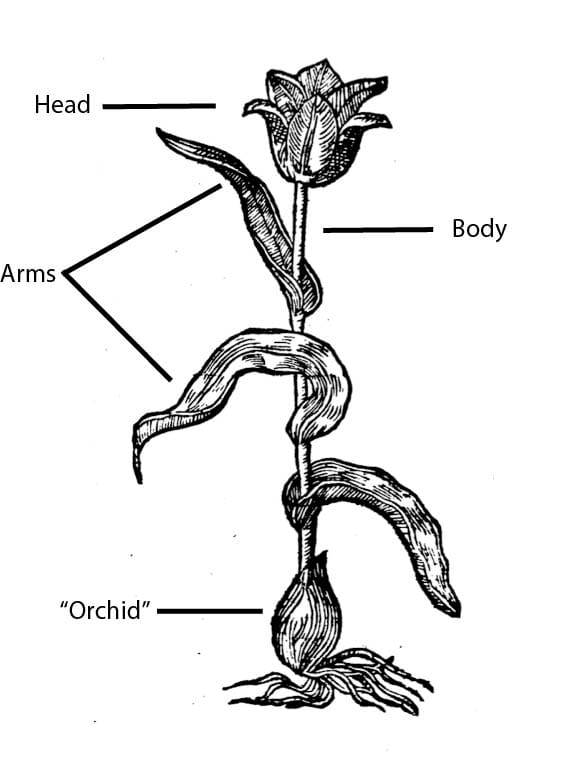

One early collective name for the pre-Linnaean family to which tulips belong to was Satyrion, because all of the flowers in the family look like little men. Satyrs were mythical creatures who were half-man / half-animal, were renown for their love of wine, music, and dancing, among other things, and who were associated with Pan and Dionysius.

Members of the Satyrion family are described after the creatures which are somewhat human because they have a head (flower), arms (leaves), body (stalk) and you guessed it, testicles (roots). Similar to the mandrake root (and its similarity to the human figure), certain flowers in the Satyrion family have been used as aphrodisiacs.

Orchids are also referred by the shape of their roots, which are similar to the aforementioned anatomy, or ὄρχις in Greek.

For those who appreciate mythic drama, the Narcissus is shockingly considered a member of the Satyrion family, even after Echo pursued Narcissus instead of Pan.

Witty Flower Children

Like the names of many flower-children of the 1960s, the naming of a flower “I support Pan” is a perfect encapsulation of their sense of humor. It’s just about as witty a name you can expect from people who named orchids after testicles, with varieties based on the reproductive anatomy of dogs, cats, foxes, and more.

Could this just be a medieval version of a "#TeamPan" versus "#TeamNarcissus"? Who knows?

The name is so simple and literal, it is beautiful. All it requires is two additional pieces of information (the botanical family is called "Satyrion", and satyrs loved partying with Pan), which they would assumed everyone would understand.

We (collectively) have failed them.

Not Fans of Pan

If the tulip originates with the idea of Pan, then there are two very valid reasons why Arabic abjad writing system languages would not use the name to describe the flower.

The first is simple: Pan famously gave the Persians panic-attacks during the Battle of Marathon against the Athenians in 490BC.

His original home was Arcadia; his cult was introduced into Athens at the time of the battle of Marathon, when he promised his assistance against the Persians if the Athenians in return would worship him. A cave was consecrated to him on the north side of the Acropolis, where he was annually honoured with a sacrifice and a torch-race (Herodotus vi. 105).

- 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica/Pan

The second is religious. Instead of a version of the pagan, hedonistic, and immoral tulipan, the word lâle contains the same letters as Allah.

An article in Economic Botany titled "Tulips: An Ornamental Crop in the Andalusian Middle Ages" (2009) shows that in the 10th - 13th century Andalusia they would have used the phrase “naryis muqawdas (water-bucket narcissus)” due to bucket-like shape of the flower .

The articles' authors quote from the 'Umda

They are called muqawdas because their flower is similar to a water-wheel bucket (qawadis), and are known in Sicily and Ifriqiyya as maqdunis, also applied to a kind of celery (karafs) also called maqdunis.

- Abu al-Jayr, 'Umda (11th-12th century)

It was either that, or:

the adjective maqdunis ("from Macedonia") referred to the "bucket narcissus" in Ifriqiya (in Western North Africa) and Sicily. 'Umda's translators think that it could be a misprint for muqawdas (water-wheel bucket) due to the similarity of both words.

It should be noted that the Arabic Narjis is not related to the tragically misunderstood mythological Narcissus, but rather Narjis, the mother of Muhammad al-Mahdi, the eschatological Twelfth Imam. While my initial impulse was to look at muqawdas / qawadis and think "holiness", which would make the name "the holy Narjis", it seems that this particular usage was actually borrowed by Arabic from the Ancient Greek κάδος (kádos), and does seem to have echo the concept of purification, like we saw with lustration.

This distinction gives us some unanswerable questions, like why was Augier Ghislain de Busbecq told in Turkey in the 1550s that the flower was called a "tulipan"? It may have more to do with his personal translator's ethnic background, than common usage among the religious Turks, who would likely call the tulip a kefe lale or a cavala lale. (Kefe is a city in Crimea, Ukraine, and Kavala is a city in Macedonia.)

How the Tulip became a Turban

Spoiler: Tulips don't look like Turbans.

The biggest misconception related to tulips is that the word is a cognate of the word turban, which comes from Old Persian, because tulips look like turbans.

Here are four sources who all describe the tortured linguistic relationship in a similar way.

tulip (n.)

well-known garden plant blooming in spring with highly colored inverted-bell-shaped flowers, 1570s, via Dutch or German tulpe, French tulipe "a tulip" (16c.), all ultimately from Turkish tülbent "turban," also "gauze, muslin," from Persian dulband "turban;" so called from the fancied resemblance of the flower to a turban.

Introduced from Turkey to Europe, where the earliest known instance of a tulip flowering in cultivation is 1559 in the garden of Johann Heinrich Herwart in Augsburg; popularized in Holland after 1587 by Clusius. The full form of the Turkish word is represented in Italian tulipano, Spanish tulipan, but the -an tended to drop in Germanic languages, where it was mistaken for a suffix.

From French tulipe, from earlier tulipan, from Ottoman Turkish دلبند (tülbent, dülbent, “cheesecloth”), from Classical Persian دلبند (dulband, “turban”). Doublet of turban.

A borrowing from Turkish.

Etymon: Turkish tul(i)band.

Formerly tulipa, tulippa, also tulipant, tulipan = French tulipan, tulipe, Italian tulipano, Spanish tulipan, Portuguese tulipa, tulippa, modern Latin tulīpa; early modern Dutch and German tulpe, Dutch tulp, Danish tulipan, Swedish tulpan; all < tul(i)band, vulgar Turkish pronunciation of Persian dulband ‘turban’, which the expanded flower of the tulip is thought to resemble: compare turban n.

New Latin tulipa, from Turkish tülbent turban — more at TURBAN

Even before realizing what the original Latin name and meaning was, based on three reasonable arguments against the commonly accepted narrative, I had found this approach to be highly improbable.

1. “Turban” has historically been the word that westerners have historically used to describe wrapped head-coverings, even when the people themselves would use a different word to describe their particular wrapped head-covering.

In the earliest Turkish dictionaries I could find, they used *other* words to describe this very apparently Turkish word. I keep using the word “wrapped”, because turban more likely comes from the Latin turbo, which means “tornado or whirlwind”, from which in French turbante would mean “wrapped around”. A cognate would be a wind “turbine”, which spins.

Apropos to nothing, “tiara” was originally the word used to describe the wrapped ancient Persian headwear, well before the term was appropriated by debutantes.

2. Turkish Turbans were all white.

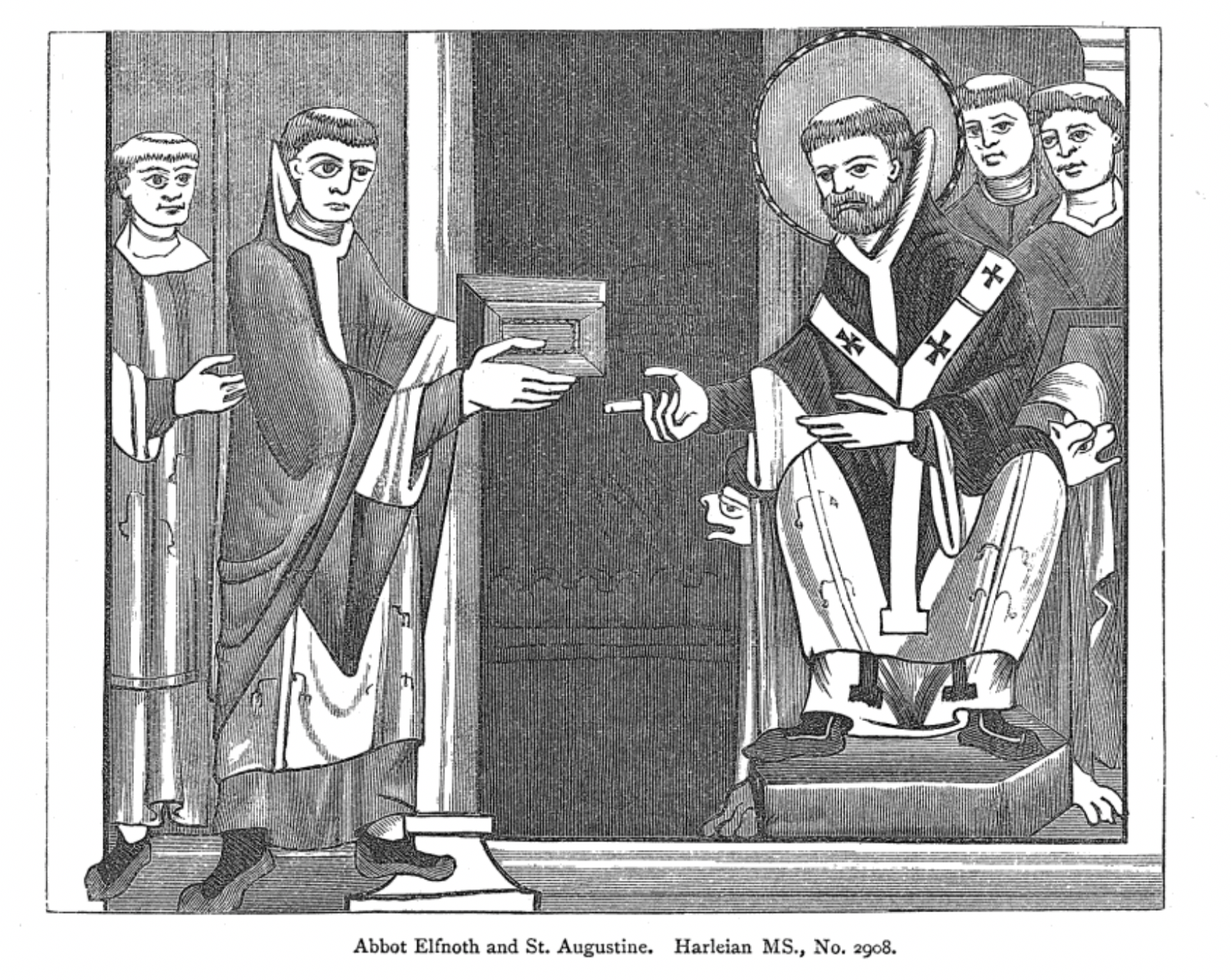

In fact, one of the “proofs” to the Turkish origin is a clear passage in a Latin letter written in the mid-16th century by the Flemish Augier Ghislain de Busbecq who visited Turkey as an emissary from the Austrian Empire to negotiate for Transylvania.

He clearly used the word tulipan (without associating it with the turban). Elsewhere, he also wrote about the fashion his Turkish hosts, noting that all their turbans were white linen, and their robes were all multi-colored.

It is most curious that they would choose to refer to a flower exemplified by its color as something which is traditionally white.

3. The 16th century sources I found about this fabulous new flower described it as “pileo dalmatico”, or a Dalmatian’s cap.

It was only later changed or switched to Turkish Cap and the turban. One of the original sources specifically wrote:

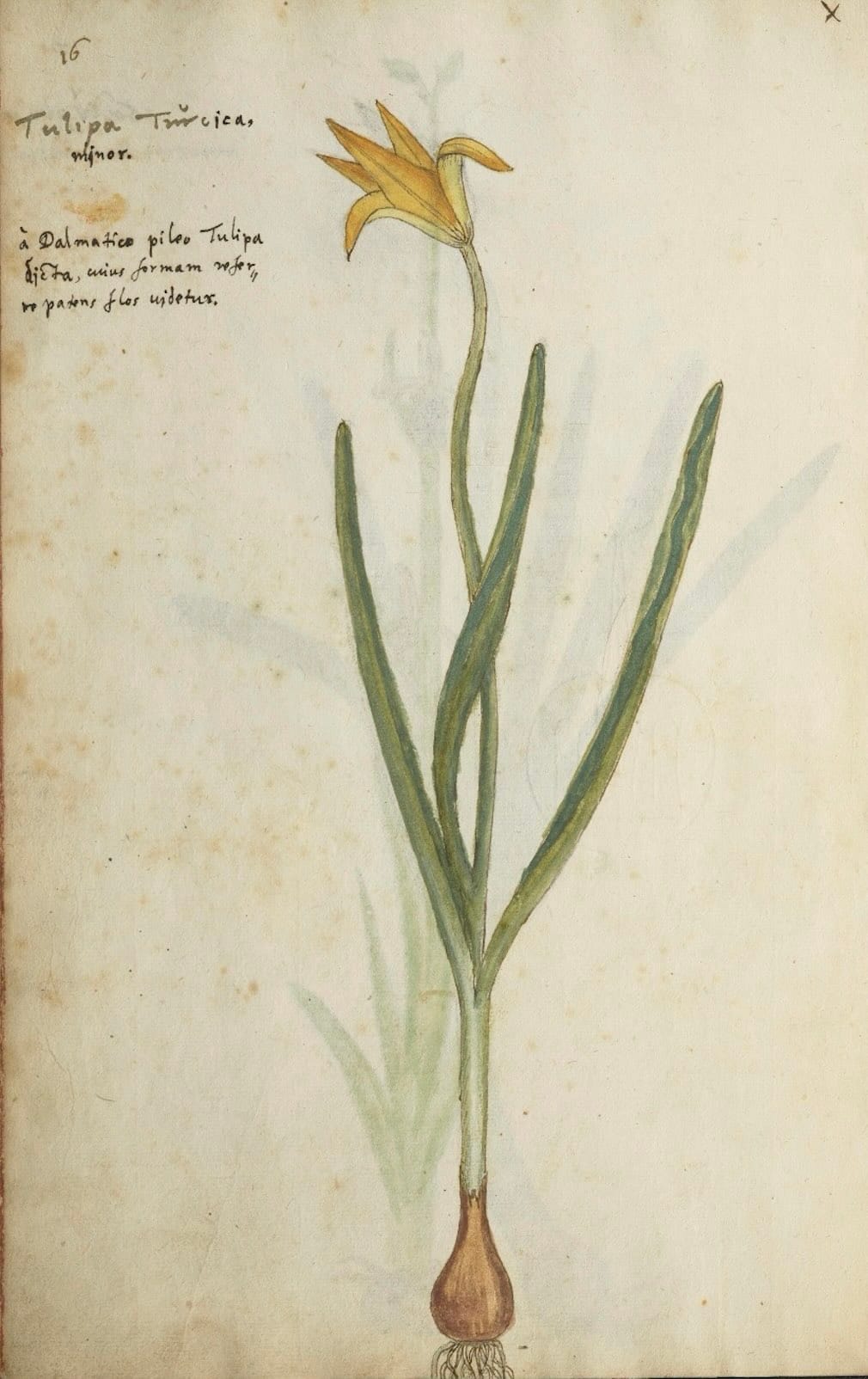

à Dalmatico pileo Tulipa dicto, cuius formam referre patens flos videtur

the tulip was described by the dalmatic hat, referring to the flower's appearance while open. (rough translation)

- Remberti Dodonaei - Florum et coronariarum - 1568

Sometimes you need to know what question to ask. At this point, my question was: Who were the Dalmatians and how was their clothing so well-known? It turns out that my question was the wrong one, but an fascinating red herring.

The Dalmatians

The Dalmatians were a people who lived in Dalmatia, and is a historical region located in modern day Croatia and Montenegro on the Adriatic Sea, who spoke a dialect of Venetian, which was derived from Latin, and were conquered by the Turks, along with the rest of Hungary, by 1537 and would remain part of the Ottoman Empire until the Venetian-Turkish war of 1714–1718. They were largely Roman Catholic.

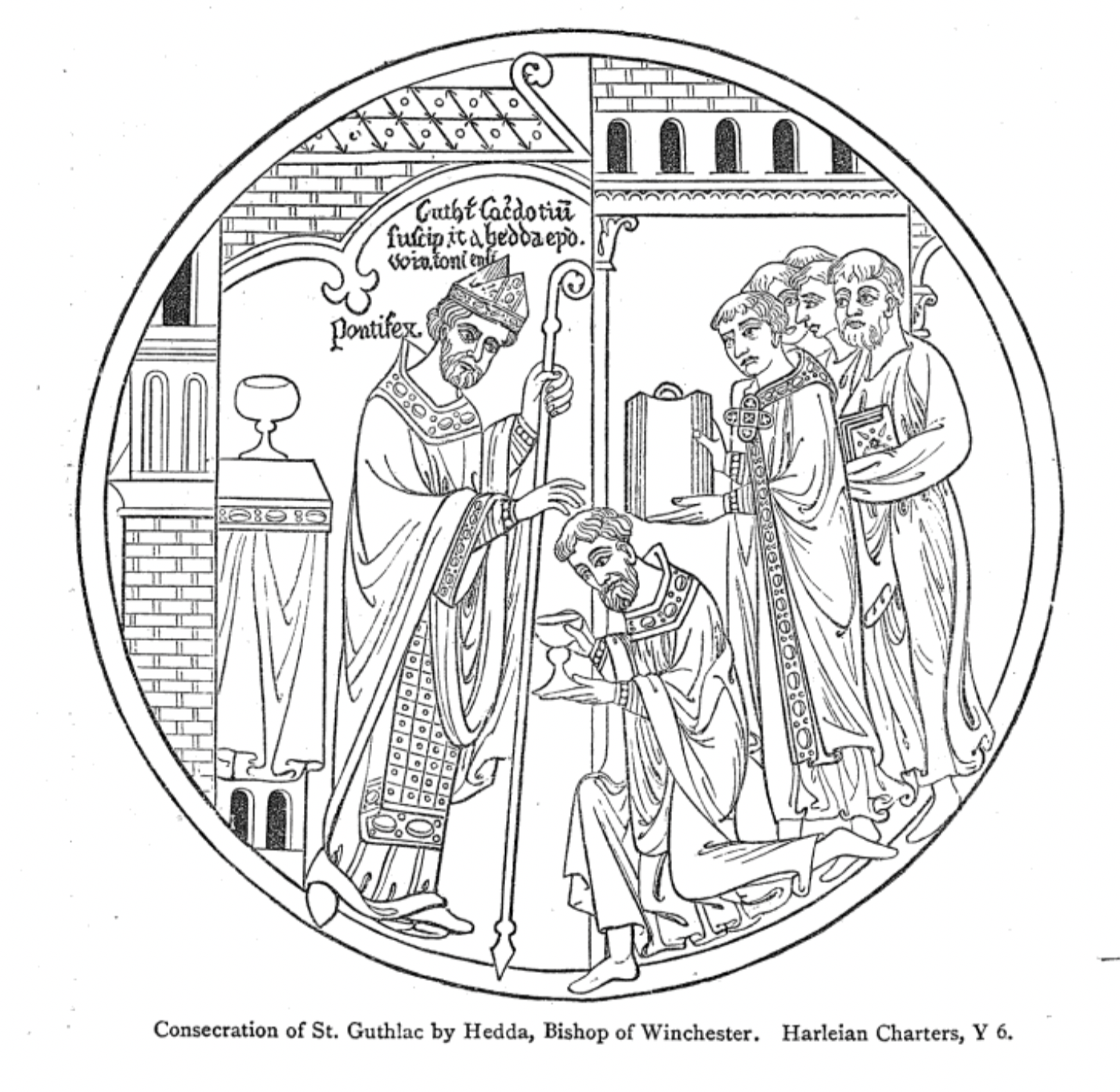

The original tribe, the Dalmatae had existed since well before the 2nd century and were known as creators of fabrics. There is a Church tunic called the “dalmatic”, which is an overgarment, creating a layered effect of color and material.

As I looked through pictures of dalmatic-clad priests, I saw more of an layered allusion to how the tulip actually opens.

If we combine this together with the journal article about the earlier Andalusian names for the flower — which were not color-based like lâle, but focused on shape, like “bucket-shaped”, we begin to see a trend of the species not originating in Persia or Turkey, but in Macedonia and Sicily. And if tulips grew in al-Andalus and the greater Iberian Peninsula, it logically would allow for continued propagation and evolution in other nearby mountainous regions, like in the Dinaric Alps mountain range of Dalmatia.

But something still bugged me.

Pileo means hat. It would be a stretch to connect it to the "over-clothing". I couldn't find any examples that had made that linguistic connection. And the Dalmatic was specifically the fabric of the tunic. The phrase "Pileo Dalmatico" makes no sense, and is not really mentioned anywhere unrelated to tulips.

And then I discovered another connection to Italy.

The First Sketch

I tracked down the first drawn Tulipa from the Codex Kentmanus, which was dated in 1548. It was by Johannes Kentmann, a German doctor born in Dresden in 1518, who had studied in medical school in Padua (Italy). During his time in Padua in the early 1540s, he would go to the gardens and sketch the flora he had never previously encountered.

Kentmann's sketch of a tulip includes, verbatim, the line about the Dalmatic cap. And you can see from the sketch what he thinks that the Dalmatic cap looks like. From the context, I'm nearly certain it means the pointed Mitre (ecclesiastic hat) which is worn with the Dalmatic tunic.

That line would be repeated, and repeated, out of context, until it became a Turkish cap and finally a turban, with the explanation that the word tulip actually means turban. All because a 20-something German medical school student in Italy chose to use a very poorly-worded phrase in Latin to describe what he was seeing.

Moreover, he must have seen or heard the word tulipano in Italian, and incorrectly decided that the proper Latin form of the word would be Tulipa.

In doing so, he missed the witty wordplay of Tulipan. And we all lost out on centuries of Pan-related visual puns.