Oh, Sušana!

A (hopefully) final newsletter about tulips.

While Tulip month officially ended a week ago, it seems that, unfortunately, my curiosity does not work well within an arbitrary limit set by the modern Gregorian calendar.

I had thought I'd experience a feeling of catharsis when sending the previous newsletter, but it had seemed that I proposed a theory about the 3000 year old history of the cultivated tulip (and its identification with the red Persian lale) that would be impossible to prove.

It seemed that my entire proof lay in biblical use of a flower called the shoshana and basing the entire connection on that. Going further down the rabbit-hole just felt like a good idea.

In this newsletter

- A 2000 year old Greek reference to the "Tulip" nickname

- Ancient Egyptian Tulips

- Tulip-Inspired Greco-Roman Architecture

- Andalusian Scarlet Tulips

Why does it matter?

If you are a subscriber, you may have already read four pieces about tulips, each often modifying or contextualizing the conclusions I had reached in an earlier piece. Why does it matter whether the shoshana / sušan was a tulip, a lily, or even a lotus? It's not (only) about being pedantic.

In uncovering millennia of wordplay, allusions, references, connotations, and more, we are able to better understand the books we consider important, and endeavor to better understand how they were intended to originally be understood.

But more importantly, if these are all referring to the same flower, and the tulip has been around for millennia, it may have inspired more art, design, & architecture, myth & poetry, and metaphor & symbolism, than perhaps any other flower.

Dioscorides

Starting with probably the single best support for my theory, a 1st century Greek pharmacologist named Dioscorides. Leaving little room for interpretation, he is very clear that the Κρινον βασιλιχον (crinon basilixon, literally the royal crinon) was red, not white.

How red was the flower? He compared it to the blood of Aries (Mars). Remember that in Greco-Roman mythology, Aries (Mars) is the god associated with Spring.

But there was another level to Dioscorides' entry for the flower. He also included a few known translations of the flower, including Shoshana (σουσινον) and the Syriac σασα (sasa). The Latin commentary in the volume I was using describes the Syriac as a corruption of ܩܘܩܢ، or literally Sušan.

It's not Greek to anyone!

And then there was a word that has confused scholars for centuries: ʾαβιβλαβον (abiblabon). A Latin commentary I read assumed it was the transliteration of the Hebrew phrase אביב לבן, and chooses to translate it as spica alba or "white-headed", which would indicate a white coloring of the flower. There were just two slight problems with that reading:

- White would have been laban, not labon.

- Especially in this context, abib is more likely Spring (the season) than "head".

In short, the word makes absolutely no sense in Greek.

When borrowing a foreign word into a Semitic language, there are some interesting things that happen. One is that a vowel would be added before the s.

- In Hebrew, "stadium' is pronounced "itstadyón".

- In Arabic, the word "studio" is pronounced "ʾistidyō".

When the ancient Greeks borrowed a word, it first would add a suffix like -εύς, -ος or -ον to the end of a noun. As an aside, my Persian grammar is not good enough to know when they would include an alif at the start of a word based on the consonants.

Two Lips

As I mentioned last week, the simplest way to look at the etymology of "tulip" was to go to the Persian for the phrase "two lips", or do lab.

If Greek would have borrowed the Persian word for lip, they would have spelled it λαβον (labon). It still doesn't explain the prefix "abib-".

It could mean either "two lips" or "Spring lips".

- We know that prefix bi- in Latin means two, and I've seen worse corruptions of words. Once we consider that the prefix α- could easily be a grammatical rule in cross-language transliteration, we are left with an unexplainable -β- which could be a transcription error.

- Or the first word is really related to the Hebrew aviv (Spring), and it was nickname.

In either case, we see a clear connection to the Persian word for lips and this flower, as one would expect with a tulip.

Additionally if Dioscorides is using multiple words (in different languages) which are all phonetically related to Susa, it's reasonable to assume that Hebrew was not the only one would described the flower as the "susanna".

Ancient Egyptian Botany

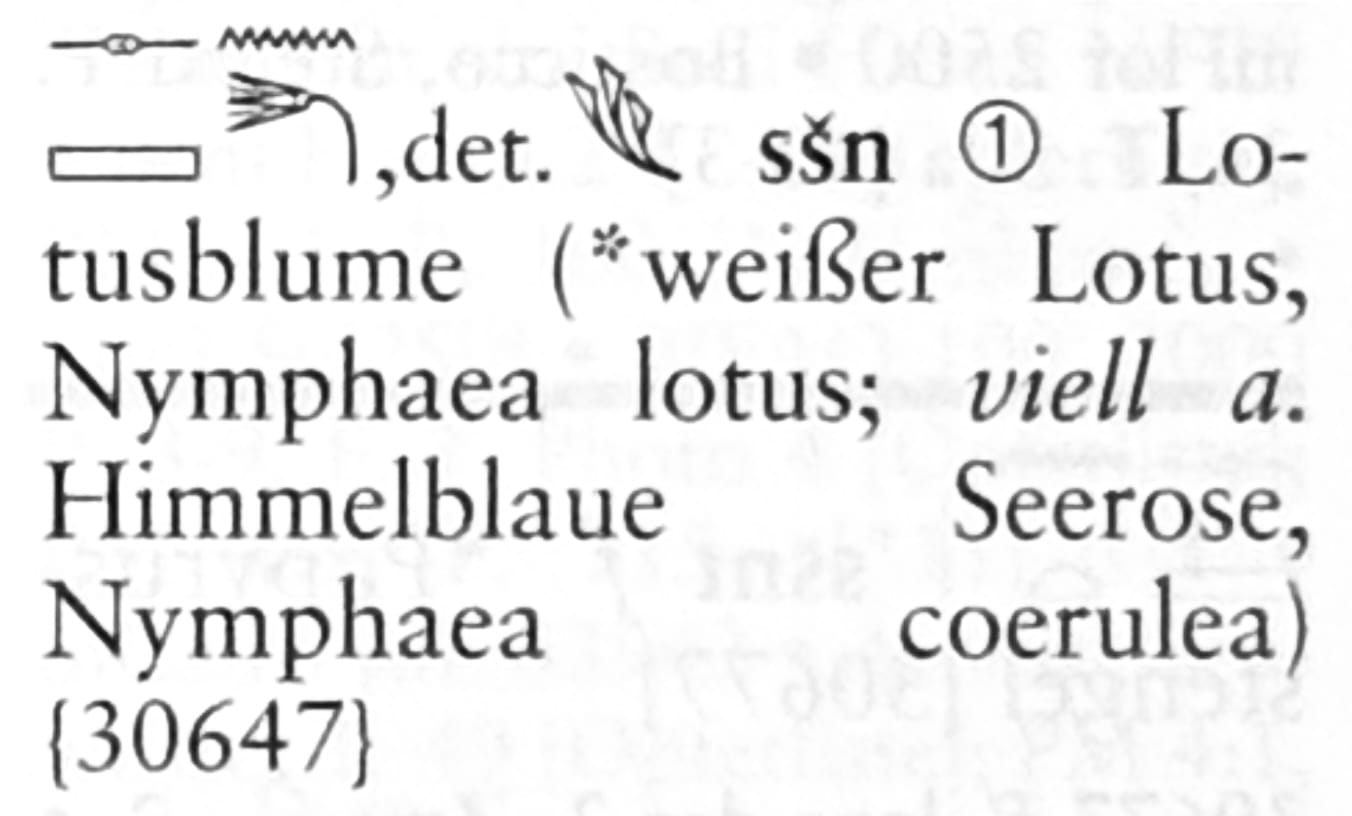

The Ancient Egyptian word named Sšn is usually translated as "lotus", but likely refers to the same flower as the biblical Shoshana.

It would have not been mentioned by Herodotus, as it wasn't an indigenous flower to Egypt, it would have been imported from Susa.

"it being planted with all sorts of fruit trees which are radiant with flowers, and its gardens having sšny (lotuses), blossoms, rushes..."

KRI IV 30, from Hoch's Semitic Words (1994, p120)

Considering that the lotus is grown in a marsh and not in a garden, it seems unlikely that that would have been flower to which they were referring. Also, the hieroglyphs look a lot more like a lale.

Greco-Roman Architecture

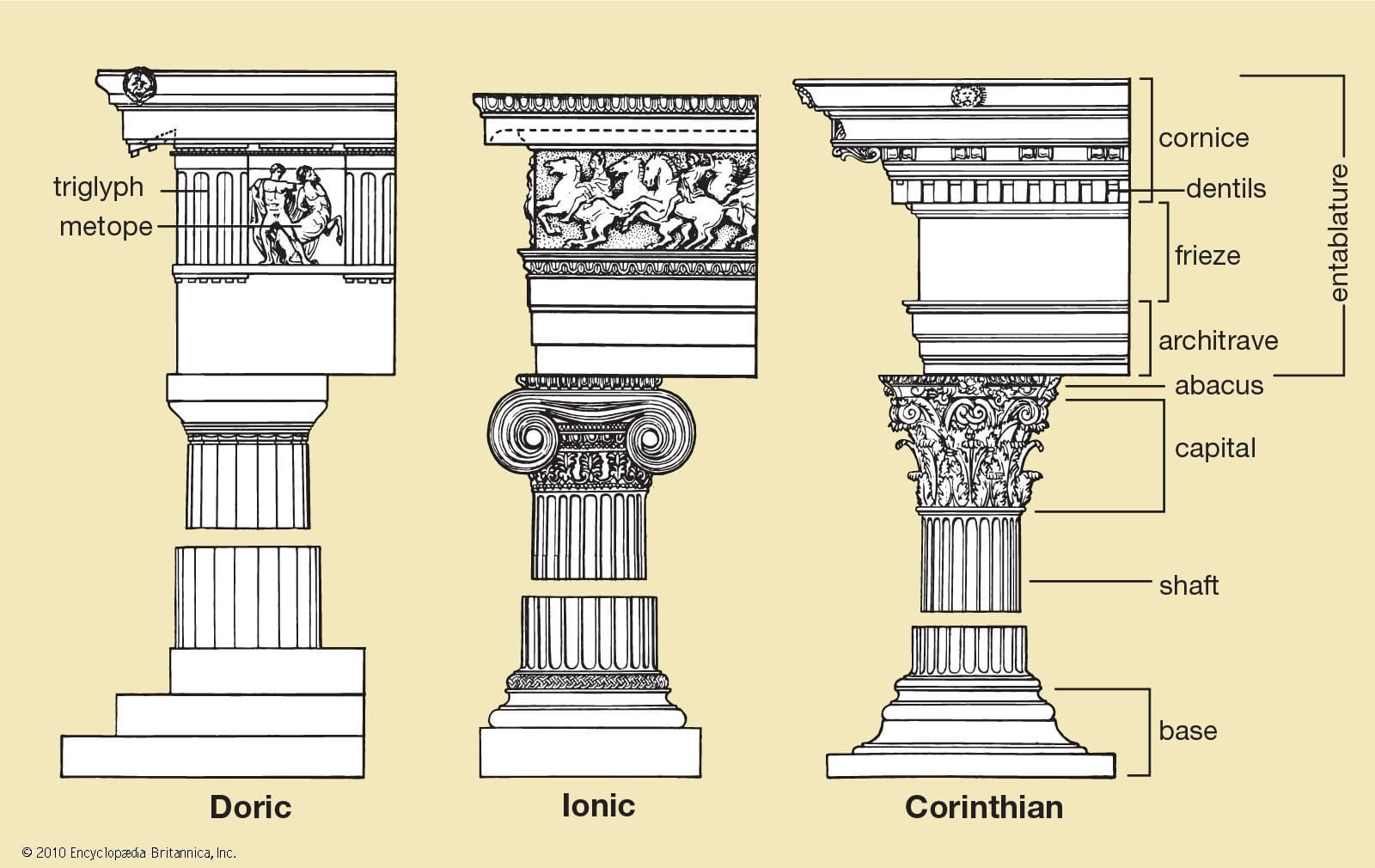

Corinthian columns may, similarly, be based on the tulip, or another red flower. Because we know that they aren't actually from Corinth. Is the word's root also connected to the Greek κρινον (crinon)?

As I mentioned last week, in 1 Kings 7, King Hiram of Tyre used the Susa flower as the inspiration for the capitals of the columns, translated by the Septuagint as κρίνου (crinou).

Vitruvius, in his writings on architecture, attributes the origin of Corinthian columns by Callimachus to have been inspired by the death of a young woman. The first Roman Corinthian column was used at the Temple of Mars Ultor in 2 CE, but the first were used at a temple for Apollo in Arcadia between 450 and 420 BCE.

I just found it interesting that Dioscorides, who wrote his book in the first century, would associate the flower with the blood of Mars. It may have been in reaction the Temple of Mars' design aesthetic and the narrative of why they decided to use Corinthian columns.

Is it possible that the floral Corinthian architectural style was in fact inspired by the κρινον (crinon), the red Persian lale, which can be associated with the blossoming young woman?

Biblical Arabic

The 10th century Jewish rabbi R' Sa'adiah Gaon was the first to translate many parts of the Bible to an early form of Judeo-Arabic. He translates shoshana to סוסאנא (sousana), which means that the Arabic-speaking populace in the 10th century understood exactly what flower this was, without any need for interpretation.

The Aramaic and Hebrew letter samekh no longer exists in the Arabic script, s0, they would use a sin, which, like Hebrew, is indistinguishable from the shin without the diacritics.

From Dioscorides to Maimonides

I can also trace Dioscorides' effect on the Mishna and Talmud, and how it potentially leads to a very curious linguistic connection between the color scarlet and tulips.

Mishna (2nd-3rd century CE)

The shared precursor to the both the Babylonian Talmud (usually described just as the Talmud), and the Palestinian Talmud, includes a line in Kelayim, the tractate on crossbreeding, about how it is not considered to be crossbreeding species when mixing between the iris, the kisum (or kisos), and the Shoshanat haMelech, or the "King's Shoshana", commonly mistranslated as the King's Lily.

It also seems at first read, that the "king" referred to in the title must be King Solomon, because he is so deeply entwined with the flower from Song of Songs. But that phrase is never previously used in Jewish or Rabbinic literature. It's most likely because the author was familiar with Dioscorides.

Talmud (4th - 6th century CE)

Palestinian Talmud The Babylonian Talmud does not have a tractate about agriculture, but the Palestinian Talmud (Kelayim 5:7) does. It explains that the third plant is translated into Greek as קרינון (crinon), which is exactly what we would assume, if this were referring to the same shoshana that we see in the Bible. It means that the word "king" isn't here to describe a different species or variety than the standard shoshana.

Babylonian Talmud The scholars of the Babylonian Talmud begin to associate the word "shoshana" with the crown, and begin to use the word to describe the top of any fruit that has a crown, like a pomegranate. There is one time where the word סאסא (sasa) is used in the same way.

This could be an indication that the scholars in Babylonia were trying to make sense of the addition of the "royal" moniker, whereas the scholars in the Land of Israel would have been familiar with the flowers.

Al-Andalus (~12th century CE)

At least one 12th century commentor from al-Andalus, Maimonides translates the Mishna's Shoshanat HaMelech with a weird medieval Judeo-Arabic phrase that had me puzzled for a while: שקאק אלנעמאן (saqiq al naaman).

I discovered that in Andalusia, they would use the word saq for fabric, so a saqiq would be a "draper" or a purveyor of fabric. And as I was leaving the University of Chicago library earlier this week, I noticed a medieval Andalusian Judeo-Arabic dictionary on the shelf, which informed me that naaman meant "choicest" or "select".

Guess what other two words can be described as "choicest" or "best" fabric?

Scarlet - Highest Quality Fabric

The word "scarlet", for expensive red fabric, was a corruption of the Andalusian سقلاط "siqillat", which could be separated into siq (or saq) and illat. Illat, similar to the Hebrew elite, refers to the best or the top. Siqillat means the best (red) fabric.

Tulipanno - Choice Fabric

When I was first analyzing the word tulip in the newsletter, and I chose to focus on the word tulipan, it was for two reasons.

- I had seen the Italian name tulipano, but assumed that it came after tulipan instead of preceding it.

- I thought that tulipanno meaning something like "choice fabric" was too outlandish a proposition. Out of all context, it was.

But tuli would be a conscious translation of a different potential meaning of κρινω (crinū), which means judgment or choice. (Panno means cloth.) And those words together sound something like "dolab" or "tulab".

Considering that this name would have been chosen when tulips were still mainly a beautiful scarlet color, it feels like an apropos name.

[-> Tulipan

By the end of the 13th century, the Italians already had access to Virgil and Ovid. They would have had access to three ancient texts with which to understand the world. This flower would have source in the Bible, a literal explanation in Dioscorides (as explained above), but they would still want to look for a mythic history of the flower in Ovid.

Enter King Midas.]

Finally, I'm not sure if this proves anything, but I thought it was interesting.

Oh, Susanna!

I had the thought that if there was a connection between the flower (shoshana) and the apocryphal character (Susanna), we would see the depictions of Susanna in red, wearing some sort of headwear. And we do!

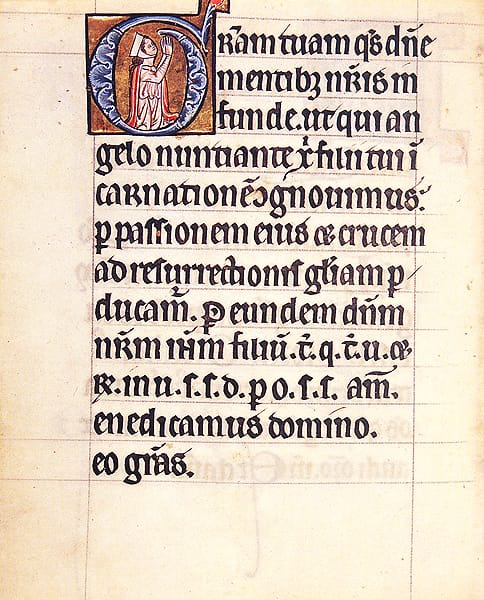

Illuminated Manuscripts (13th - 16th centuries, Europe)

Solomon, Susannah, and Midas were all popular subjects of Renaissance artists, for different reasons. If we decide to focus solely on manuscripts of prayer books and books of hours, we can see a trend throughout many medieval illuminated manuscripts. As you can see, Susanna is often depicted wearing a red dress and some sort of headwear that could theoretically be described as "tulip-like".