Color Researcher Develops Theory to Solve Millennia Old Mystery about Lithuanian Blue

How did they make blue glass beads in Lithuania in the 1st century?

Earlier this week I visited The Old Arsenal, which is the archeology branch of the National Museum of Lithuania, and I discovered something incredible which doesn't seem to have any much information about: The lost art of ancient Lithuanian blue glass making.

The original purpose of my visit was to view specimens of pottery discovered in different regions of Lithuania, in order to better understand the particular characteristics of the local clay. I appreciated how the museum's curators provided a veritable timeline of the material history of when different metals and artisanal processes were discovered or imported by the local tribes.

No Gold

One material which seemed conspicuously missing from the museum is gold. In earlier research, I had noticed the distinction between how each culture referred to gold, either choosing to focus on the process with which it was mined and appeared in raw metallic form, or alternatively to highlight the purified and polished resulting version. Additionally, in the Nahuatl language, I had noticed that it was nearly synonymous with the word for the color yellow.

In the Lithuanian language, auksas (gold) seems to be more related to the idea of offering, sacrifice or contribution (auka / aukoti), highlighting its functional cultural value. It also underscores that gold is not native to the region. It's precisely because of this that I would feel comfortable to make linguistic comparisons to Latin, for example. We've previously seen in Ovid's humorous retelling of the Midas myth in his Metamorphoses that the words for gold and ear are very similar, and we can observe the same phenomenon in Lithuanian. It may be connected to the golden earrings which may have been the first examples of functional golden jewelry they would have encountered.

Amber

Lithuania has its own version of a locally sourced natural resource which would comfortably translate into the entire range of golden colors: gintaras, or what we would call in English, amber. Like gold (and honey, for that matter), amber's hues range from yellow to red.

The National Museum featured several examples of necklaces, pins, and other forms of excavated jewelry featuring the mineral. In fact, a few years ago, they even had an entire exhibition about the Amber Road from Rome to the Baltics.

Lithuanian Blue

Amber is so valued by the culture, and rightfully so, it is understandable that they would overlook perhaps a greater example of early Lithuanian innovation; one that belongs in the annals of color history alongside Egyptian blue, Biblical tekhelet, Indian blue, Persian blue, Italian ultramarine, French pastel, indigo, Prussian blue, the synthetic blues of the second half of the 19th century, and IKB (International Klein Blue) by Yves Klein: namely Lithuanian blue glass beads.

The moment I saw a necklace featuring both beads of polished amber and beautiful Lithuanian blue glass, I needed to know, how did they make the blue glass?

I went the museum research library and spent several hours with a few very helpful librarians going through volumes of books trying to identify the process. We found many examples of jewelry featuring only polished amber and Lithuanian blue glass, as early the first centuries of the Common Era, but nothing that would explain the process.

The internet provided no real assistance.

Cobalt Required

Put simply, the problem is the following: the only metal that there seemed to be used locally during the earliest time period was iron. And using iron in the glassmaking process would result in green glass, not blue glass. Blue glass would likely need cobalt.

On an educated whim, I searched for the cobalt levels in various types of Lithuanian clay, and found that that the highest levels of exceeded 6%.

Experiments

The following day I went to the national research library and explored volumes of the 2017 journal of the Lithuanian Experimental Archeology Club.

One article ("Glass Beads in Lithuanian Archaeological Materials of 2nd–12/13th centuries and reconstructive and technological aspects of their production") included paragraphs about the history of Roman glassmaking practices, but nothing about Lithuanian artisans. Though, it was validating to read that the consensus is that the blue glass beads were most likely created locally, and not imported. (Source #1)

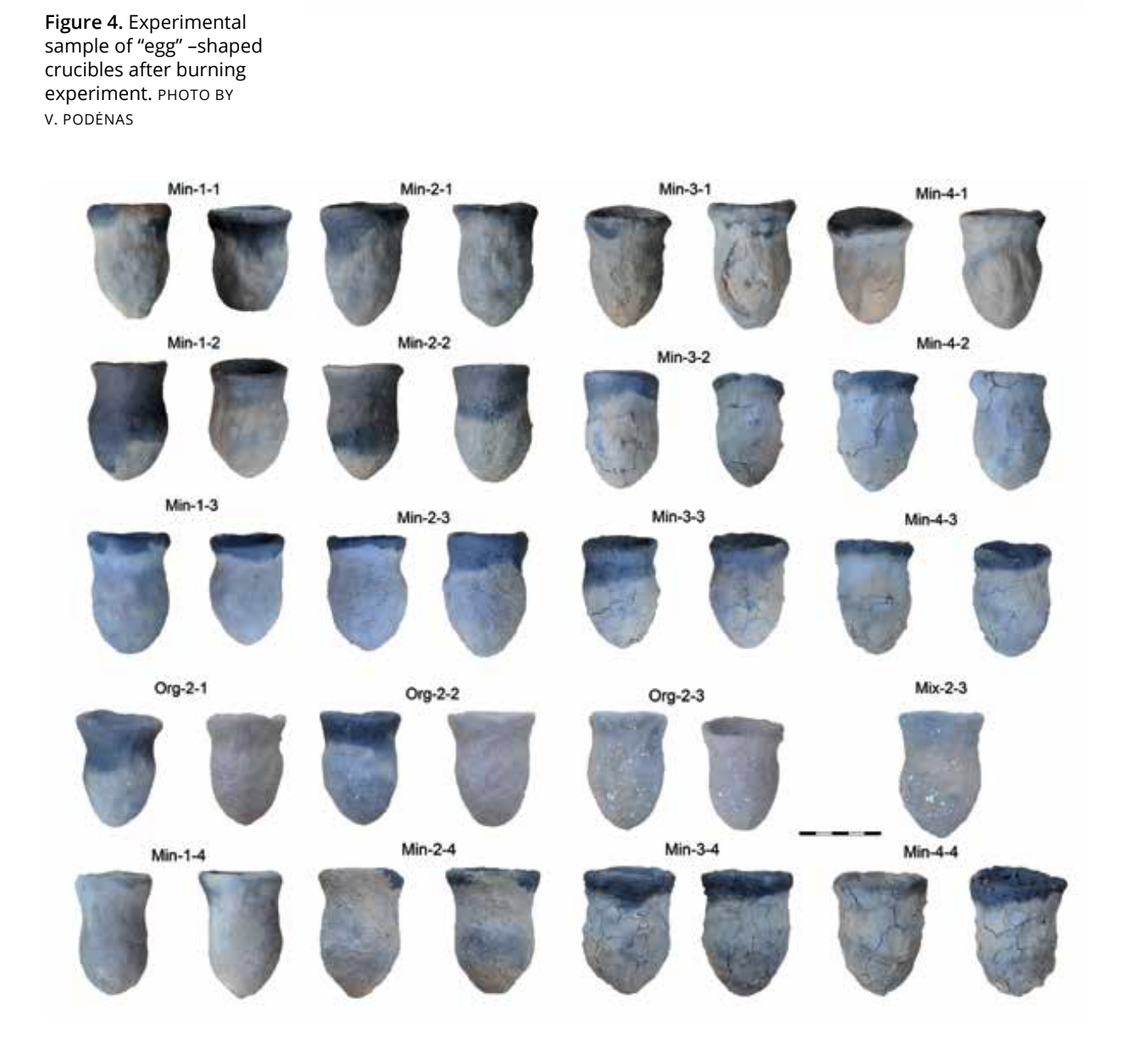

A different journal article ("Experimental investigation of color metallurgy according to crucibles discovered in Narkūnai") in which they were trying to identify the uses for various designs of locally made clay crucibles featured an image of the post-kiln crucibles, before they were used. Several of the crucibles seemed to have some light blue glaze, something that wasn't mentioned in the article, which would indicate that it was something which already existed in the clay.

Color Words

With several obvious notable exceptions, there tend to be two general categories of color-words:

- The first is for what the color resembles in the world. Sage green is a shade of green that resembles the color of sage; no sage is harmed in the making of the pigment.

Since the expansion of the synthetic pigments and dyes in the 20th century, most color-words fall into this category. - The second category is related to the name of the source or the processed pigment or dye of the color. By tautological definition, something can only be indigo-colored if the processed result of the indigofera tinctoria plant is used, otherwise, it's just a sparkling blue.

Some Lithuanian Color Words

Three quick notes about the Lithuanian language which may provide some context about the next section:

- Lithuanian is considered to be a very old language, which is not derived from Greek, Latin, German, Russian, or Old Norse.

- There are not many extant pre-17th century texts with the language.

- Its original orthography (letters) was definitely not Latin.

It's not Greek to me

The general word for the color blue, mėlyna, is found in the earliest texts I've found. The general consensus of the etymologists seems to be that the word comes from Ancient Greek, where μέλας (melas) meant dark or black. We see the word used in things like "melancholy".

Considering that scholars have long misunderstood how the Greeks perceived color, specifically blue, it is very enticing to assume that the Lithuanian word originates there.

Clay

The most basic word for clay in Lithuanian is mėle, with the common material description being called molis.

It's quite obvious that my original theory was that blue is connected to the word for clay, which is why I set out looking for blue clay, which would be part of the first category of color-words.

An example of a Lithuanian color-word based on similarity is the word pilka, meaning grey. The word for mouse is pelē. (1)

Taking inspiration from my understanding of Semitic languages, if we focus on consonants and accept that vowels are going to change based on form and letters, we can observe either an N or a K added in these several basic cases, with the same process occurring. (2)

- RD (ruda, ore, noun) and RDN (raudona, red, adjective, pigment)

- ML (mėle, clay, noun) and MLN (mėlyna, blue, adjective, pigment)

- PL (pelē, mouse, noun) and PLK (pilka, grey, adjective, similarity)

If the original red pigment was made from ore, it would follow that the original blue pigment was extracted from clay, and would only make sense if it was referring to clay with relatively high cobalt levels which was commonly found in the region.

Which would mean that they had developed a unique process to make that work. Which is why it would be valued on the same level as amber. And they didn't seem to have other colors they did this with.

As there don't seem to be any other very blue objects, I would contend that beads are the reason mėlyna is the predominant blue, as opposed to žydra, which is sky-blue or azure.

Similar to English and German, where blue is related to blooming flowers, so too, žydeti is the verb "to bloom or blossom". Additionally, the noun for flower is gėlė, which is somehow related to the words for iron, geležis and yellow, geltona. (3)

Conclusions

- Lithuanian blue glass is not a theory. It is something that has existed for literal millennia unheralded for its richness, which was overlooked because of the amber. As I mentioned above, Lithuanian researchers seem not to know how it was made, so I feel safe referring to it as a 2000 year old mystery.

- Linguistically, there is a connection in Lithuanian between the words for clay and blue. This seems to not be found in other languages, which would indicate that there is something unique about the Lithuanian clay.

- We known that some fired Lithuanian clay possesses a blue hue.

- This is only a theory because in order to prove we would have to see 1) how cobalt could be extracted from Lithuanian clay and 2) if that cobalt could be used in glassmaking. (4)

- Considering how Vilnius had turned the simple šaltibarščiai (cold borscht) into an entire Pink Soup Festival, it's fun to imagine how Lithuania would embrace the lost tradition of Lithuanian blue glass, however it is made.

Footnotes

- I'm assuming the "-ka" functions as a diminutive like the Russian "-ик (ik)" or "-ка", for that matter.

- If we did the same thing in English, we could see a similar pattern:

GR (grow, verb) and GRN (green, adjective)

BR (bear, noun) and BRN (brown, adjective)

This, of course, plays into the theory that "bear" was simply a euphemism for the real name that they were too scared to mention. - According to my theory, geltona is likely the word for the yellow pigment that comes from dyer's weed, not a similarity to flowers. And perhaps žydra comes from the pigment derived from woad, which is then extended to the sky-blue.

- Alternatively, I would be very happy to be disproved by someone showing how else blue glass could have been produced with the materials available locally around the 1st century of the Common Era.

Quoted Sources

Emphasis added

Bliujūtė, Justina, "Glass Beads in Lithuanian Archaeological Materials of 2nd–12/13th centuries and reconstructive and technological aspects of their production" in "Experimental Archeology", I, Vilnius, 2017

GOOGLE TRANSLATED FROM LITHUANIAN

Glass beads were produced in more than one workshop, but studies of their chemical composition show that they were made from glass raw material, melted from similar components according to a set recipe (Bagdzevičienė et al., 2013, pp. 183–185, table 1). The color range and shapes of the beads are identical or quite close. Studies of the chemical composition of beads found in Lithuania from the Roman and Migration Periods have not been carried out.

We must rely on the widely known statements in historiography that the places of production of the beads are the western and eastern provinces of the Roman Empire (the eastern Mediterranean coast, the Middle East, the Black Sea coastal cities and Egypt), and later the Byzantine Empire. The production of glass beads was limited to the northern border of the Roman Empire.

ENGLISH SUMMARY

We still have quite one-sided knowledge concerning Lithuanian glass beads, which is based on their typological studies (shape, size, color, clarity), and their spread in the current territory of Lithuania or in the Baltic countries. In recent decades, the attention was drawn to the wearing of strings of beads and individual beads, their composition (glass, amber and metal beads and pendants), their coherence with other costume elements, as well as their meaning in expressing personal social status, and costume of certain cultural area or tribe.

We do not have knowledge about faience and / or glass beads from early metals period. In the territory of western Balt culture between the Paslenka (Pasargė) river in southwest and Dauguva river in the north – the glass beads become popular in the 2nd century. Glass beads were spread unequally. According to archaeological material, the largest spread of glass beads was in the Roman period, with a considerable decline during the Migration period. In Viking times, glass beads were mostly worn by Curonians and Scalvians, comparing with the other Balts tribes.

In Lithuania glass beads in strings and in single begin to spread in 8th century. According to the data of 1981, beads of 8th–11/12th centuries were found in 81 places in Lithuania, with about 4,000 glass beads among them. However, the main finding places of glass beads are concentrated in Curonian lands of Pilsotas, Mėguva and Ceklius. The other glass beads concentration is clearly visible in the lower reaches of Nemunas and on the left bank of Jūra midstream, in Samogitian burial sites. The similarity of beads colors to the forms to the beads spread in large areas of Europe and the Middle East suggests that part of the multicolored beads were made in Scandinavian Viking centers or were re-exported from them to the Eastern Baltic Sea region. Moreover, judging by a particularly large concentration of blue, transparent and notched beads in Western Lithuania, we can assume that part of these beads were produced locally from imported glass preforms (raw materials).