King Midas - The Tulip's Forgotten Namesake

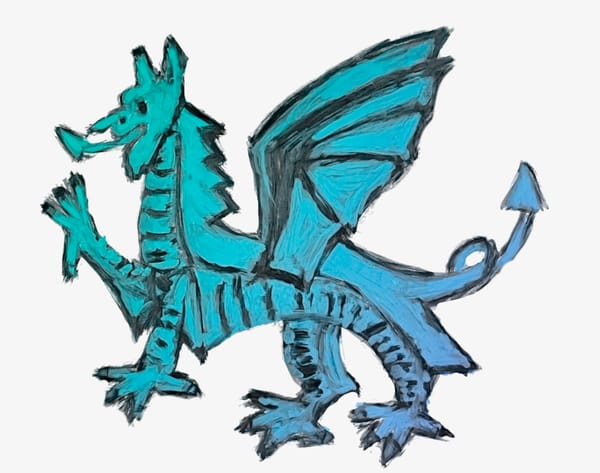

King Midas voted for Pan, and Apollo became so enraged, he turned Midas' ears into donkeys' ears. Midas was embarrassed and tried to hide up the ears by wearing some sort of head covering, which likely resembled the tulip in a closed state.

I’m happy to announce that I’ve discovered who the tulip was named for, and he is the perfect vehicle to take us from the Italian Renaissance and into the Dutch Golden Age and the so-called Tulipmania of the 1630s, next week.

Last week, I put the forth the theory that the word tulip isn’t from any derivation of turban, but rather from a rather literal reading of the probable original Latin form - “TULI + PAN”, meaning, “I’ve supported Pan”.

Why would a flower be described as a supporter of Pan, beyond the underwhelming generic explanation of “the types of flowers are called satyrions and the satyrs liked Pan”?

The answer is simple: The flower was named for King Midas.

King Midas

When we usually hear the name King Midas, we immediately associate him with the first part of the myth written about in Ovid’s Metamorphoses.

He was an ancient Phrygian king who loved gold, who made a deal with Dionysius, and subsequently everything he touched turned solid gold. Within days he regretted the deal, as he was unable to eat anything without it turning into gold. Dionysius purportedly undid the deal, and Midas left the city. He began to live in forests, separated from humanity, and appreciate rustic, unvarnished nature. And it was on that backdrop did the second part of Ovid’s Metamorphoses take place.

Another forest denizen, the god Pan, had recently created his eponymous flute, and had taken to playing it. Another god, Apollo had heard Pan playing, and challenged him to a musical competition. The mountain Tmolus was purportedly the judge. The difference in the music was literally the heaven and earth. Apollo channelled heaven into playing the most ethereal song ever heard. And Pan played his earthly flute.

Tmolus declared Apollo the champion, but another person at the the competition disagreed. King Midas voted for Pan. He preferred the rustic melody. Apollo, not known for his love of being disrespected, questioned Midas’ ability to hear, and elongated his human ears into a pair of long, floppy donkey’s ears.

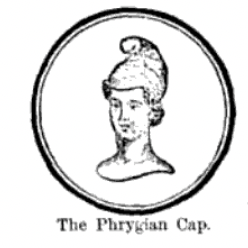

Midas proceeded to attempt to hide his apparent deformity by wrapping his head in purple fabric. The word to describe the headcovering in that version was a form of tiara. Unlike our modern understanding of tiara, which may be given to the winner of a beauty competition, the tiara initially referred to the wrapped hat of the Persian monarchs, a word we would more like translate as “turban” today.

Therefore, reading the name as “TULI + PAN” or “I voted for Pan” is the explanation why Midas needed to wrap his ears in the first place.

There is another level to the Ovid story which is delightful wordplay, namely the connection between a king who was obsessed with gold and his ultimate "punishment" of being afflicted with donkeys' ears. In Latin, the noun "aurī" could refer to two different, unrelated words. It's either the genitive singular of aurum ("gold") or the dative singular of auris ("ears"). A really fun intersection between both words is "earring", which is an inauris, something with no ears is called "inauritus", and "inauro" means "to gild".

Avid Readers of Ovid

A year ago, when I wrote about orange carrots and the Dutch Golden Age, I noted:

While we associate orange to be the color associated with the Dutch, in fact, the concept of the de Gouden Eeuw (The Golden Age, translated from the Latin aurea aetas) was used to describe the 17th century, already from Joachim Wtewael's 1605 painting "The Golden Age", inspired by a Dutch translation of Ovid's Metamorphoses.

While our current association with Midas is his touch of gold, there are dozens of works of art between 1400 and 1700 which are titled the "the judgment of Midas", which were all depictions of the Apollo and Pan competition. And they were all inspired by Ovid.

Why Did We Forget The Origin?

If King Midas was so remembered between 1400 and 1700, how did it happen that people just forgot that the name was 1) Tulipan from "tuli + pan" and that 2) the flower looked like Midas wearing a hat to cover his donkey ears? We know they knew the story.

While I would be tempted to say that its because King Midas was so associated with the golden touch, if the flower had been named with his name, it would have immediately been associated with a golden color, which would have been incorrect.

Instead, I think three unrelated things happened:

- Midas became so associated with the donkeys' ears, it would have been weird not to paint them (and cover them up with a cap).

- In artistic depictions, the wrapped tiara of Ovid became a contemporary version of tiara or crown.

- People began to associate the tulip with the open blooming state, not the closed state.

The Foolish King With The Donkey Ears

If I were to reference the monarch with the donkey ears, knowing everything we know now, you'd immediately associate it with King Midas. Especially after reading the earlier part of this newsletter.

But the Foolish King with Donkey Ears myth had been used as metaphor for millennia. For example, when the ancient artist Apelles wanted to depict the foolish king at his slander trial, he chose to include donkey's ears, even though he wasn't depicting Midas, per se. But he was most likely referencing him.

"On the right of it sits a man with very large ears, almost like those of Midas, extending his hand to Slander while she is still at some distance from him."

– Lucian, with an English Translation by A. M. Harmon, 1913

In fact, when Leon Battista Alberti who wrote Della Pittura / De Pictura ("On Painting") in the 1430s suggested that artists reproduce this lost masterpiece, he described the king as

Erat enim vir unus cuius aures ingentes extaban

there was a man whose ears were enormous

without ever mentioning the association with Midas.

When artists during the Italian Renaissance began reproducing the lost work, "The Calumny (Slander) of Apelles", including Botticelli, after a slander trial of his own in the 1490s, and scholars seem to point out additional details that reveal the connection to Midas.

Over the following centuries, the trend of depicting King Midas (in the plethora of works called "The Judgment of Midas") with large donkeys' ears and a circular crown-like tiara went from Italy to France, Germany, the Netherlands, and England.

Which means that one who named the tulipan was following Ovid's written description, not any artists' representation.

Lover of Hats

The tulip as Midas explains the seemingly inherent connection between tulips and hats. Even Kentmann’s misuse of the word Dalmatic, when he intended to describe the mitre when the flower had bloomed, makes sense.

It explains, as well, why I had noticed a lot of people referring to the flower’s cap as a Phygrian hat, later called a “Liberty Hat”, because King Midas was the Phrygian king. And finally, it explains the connection to the turban.

Before the flower blooms and it stands tall and closed, it seems like the perfect description of a donkeys’ ears wrapped by fabric.

A Tulip By Any Other Shape

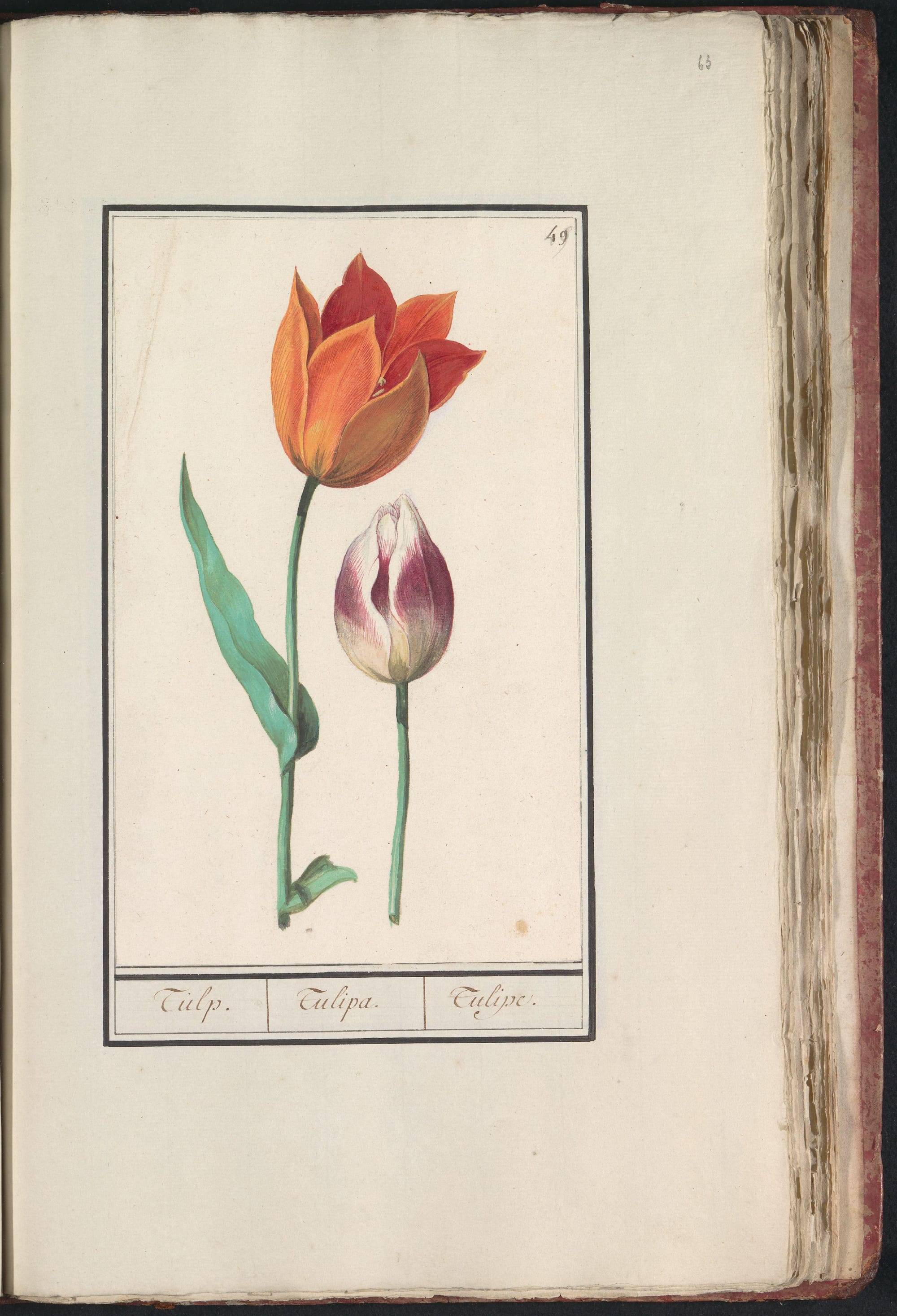

There was an evolution in the depiction of the tulip itself, from the closed state, which is likely a lot more similar to what inspired the connection to King Midas, to the open state of bloom, which, while visually beautiful, bears little resemblance to Midas.

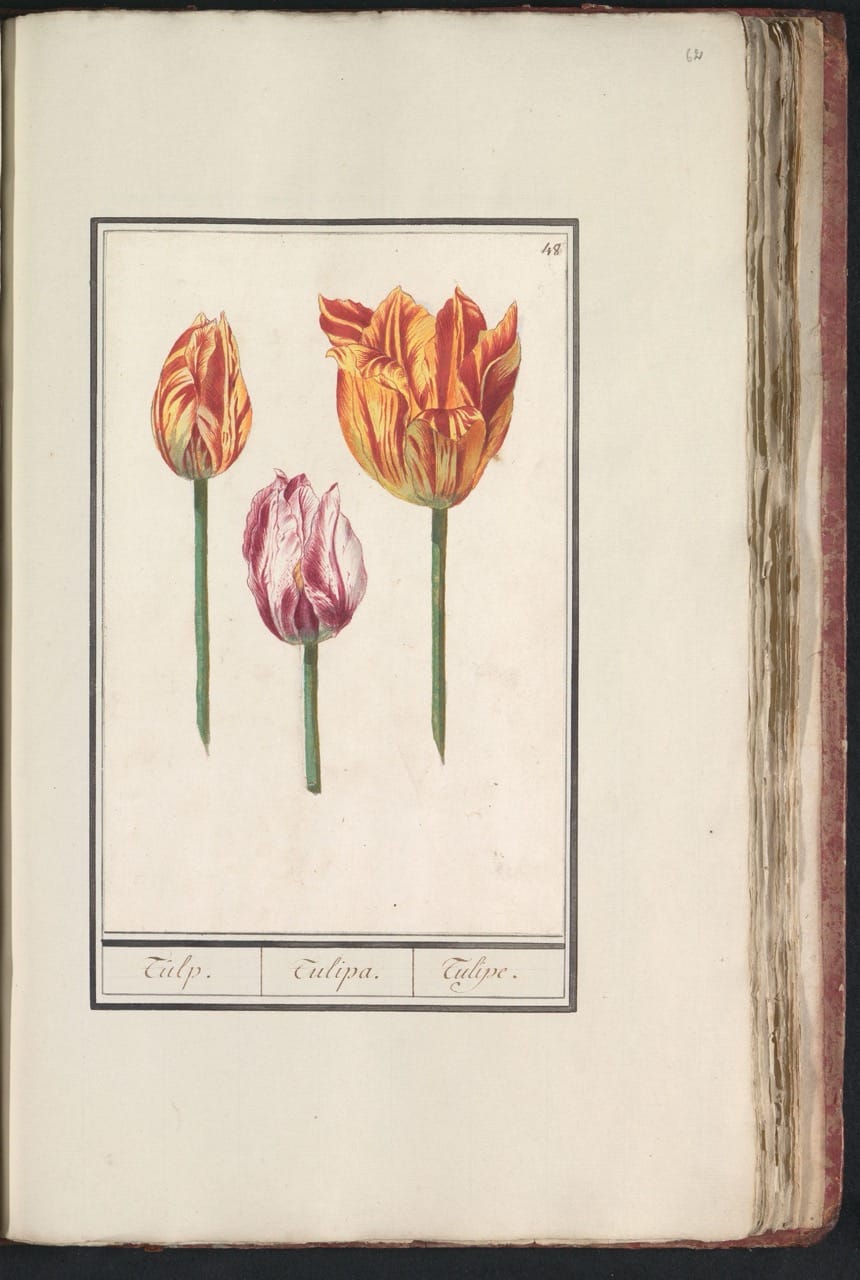

Even over the course of 30 years, we see a series of tulips by Anselmus Boëtius de Boodt from between 1596 - 1610 to depict the flower in a closed state as well as as in an open state of blooming.

However, by the time we have Jacob Marrell circa 1640, he seemed to only depict them in the open state of blooming.

While the flower probably lost its connection to Midas late 15th century or early 16th century, it is quite logical that they saw the closed flowers and compared it Midas' Phyrgian hat. I can imagine the young Dr. Kentmannus being told that it resembles a hat, and as he saw the flower in a state of bloom, he compared it to the mitre.