A Doctor's Advice*

* Dr. Seuss published more than 60 books in his life, won an Academy Award, a Pulitzer, and several Primetime Emmys. He also has a medical school named after him.

As 2024 comes to an end, I thought it be prudent to find some sage wisdom to share.

I immediately thought of Dr. Seuss.

The problem was that he had published a lot, and due to copyright laws and availability of source materials, the last few weeks of the year is the worst time to begin researching someone from the 20th century.

So I decided to focus on his first children's book, And to Think That I Saw it On Mulberry Street (1937), and the final children's book published in his lifetime, Oh, the Places You'll Go! (1990).

Was he really a doctor?

Dr. Seuss is obviously a pen name for Theodor Seuss Geisel, who dropped out of a doctoral program in English literature from Lincoln College at Oxford, so he never officially received the degree. His final straw was a hearing two-hour lecture about punctuational differences in folios of Shakespeare's King Lear.

That said, his American alma mater Dartmouth awarded him a Doctorate in Humane Letters in 1955, stating:

as author and artist you single-handedly have stood as St. George between a generation of exhausted parents and the demon dragon of unexhausted children on a rainy day.

Misunderstood Dragons

A few salient notes on dragons and art:

- Dr. Seuss accidentally became famous after creating a cartoon for Judge magazine, which was a dragon-insecticide joke.

"It was a picture of a knight who had gone to bed. He had stacked his armor beside the bed. There was this covered canopy over the bed, and a tremendous dragon was sort of nuzzling him. He looked up and said, 'Darn it all, another Dragon. And just after I'd sprayed the entire castle with Flit. (an insecticide brand).'"

The wife of the advertising executive of the Flit account randomly saw this cartoon after she couldn't get an appointment at her favorite hairdresser, and after weeks of constant haranguing, convinced her husband to hire Geisel.

Flit was owned by Standard Oil of New Jersey, who also hired him to advertise Esso Marine, and the exclusive contract forbade him from doing a lot of outside work.

Which is why he began writing children's books. - The Cat in the Hat was published two years later in 1957, which featured the real culprit behind the activities of "unexhausted children on a rainy day", and it wasn't a dragon, but a Cat in a Hat, and a pair of troublesome Things.

- Completely unrelated, I researched St. George and the Dragon a few months ago (for a proposal for a British art history research grant), and discovered:

- One of the books published by the first English printer William Caxton was a translation of lives of the (Catholic) saints, which included woodcut illustrations from a Dutch artist, which ended up being copied as frescos on the walls of many British churches.

- During the Reformation, Henry VIII banned all the Catholic saints, which resulted in churches whitewashing their walls, some of them only to be discovered hundreds of years later.

- One of these images was a depiction of St. George and the Dragon found in a Welsh church around 2009, which made no sense, because the Welsh liked Dragons.

- (Welsh) King Henry VIII (if I'm not mistaken) also removed the depiction of St. George and the dragon from The Most Noble Order of the Garter.

- Raphael (the artist, not the Ninja Turtle) painted two versions of St. George and the Dragon, the second one in honor of his patron who was inducted into the Order of the Garter.

- In Raphael's versions, St. George was holding either a sword or a lance, not Flit insecticide.

Some Seussian Color

Early Constraints

While there is a lot of research to be done about Dr. Seuss and color, most of his books before 1963 were created using a 4-color printing system, that did not blend or mix colors.

Which meant, if the four colors were blue, yellow, red, and black, there would not be green in the book. I believe that this means that in a book like Green Eggs and Ham (1960), where both the eggs and ham are green, green would be one of the colors used. (He famously drew an entire color map for each book, which I would love to get access to.)

This is not true for the 1937 And to Think That I Saw it On Mulberry Street, which does have touches of green in it, in addition to blue, yellow, and red.

Fantastical Animals

The old adage of "the zookeeper's son is unable to draw realistic pictures of animals" rings true regarding Dr. Seuss, which is why he decided to create his own fantastical creatures.

In Mulberry Street, the zebra (which is naturally either a white animal with black stripes or a black animal with white stripes) is depicted as a yellow animal with black stripes.

When Seuss was at Oxford, he illustrated a lot of John Milton's Paradise Lost, spending a significant amount of time on Adam and Eve. Apparently inspired by Adam, throughout his career, he would name many, many animals from his imagination.

Drawing fantastical animals did help him find love, though. His first wife, Helen, "picked him up" during one lecture by looking at his notebook and saying "I think that's a very good flying cow."

In 1959, "Helen Geisel, Ted's chief editor, chief critic, business manager and wife" was quoted in LIFE magazine as saying "His mind had never grown up. Ted doesn't sit down and write for children. He writes to amuse himself. Luckily, what amuses him also amuses them."

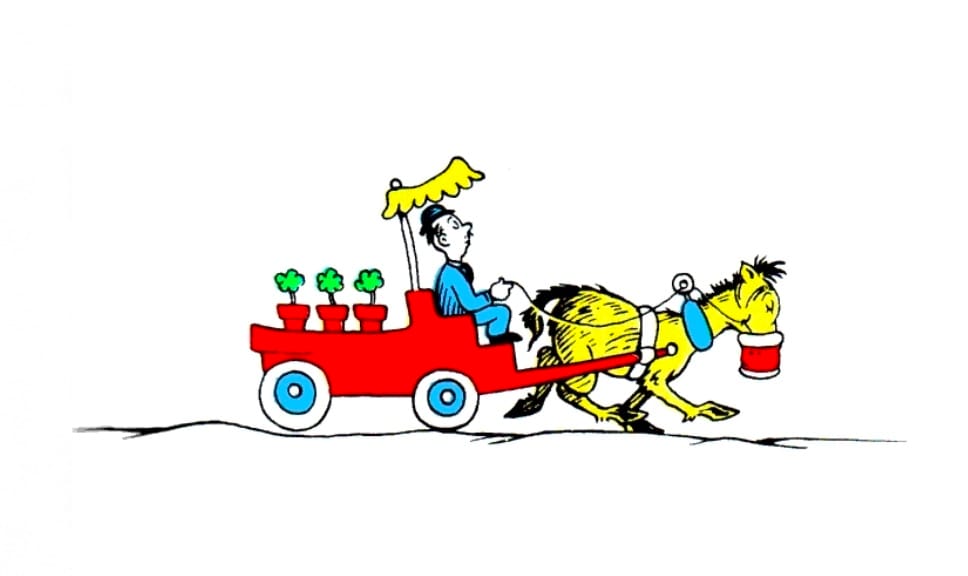

Two Interpretations of Mulberry Street

Reading #1 - Imagination is good.

It is the story of a boy, Marco, whose father warns him not to tell fantastical stories. and in a style which becomes very stereotypically Seussian, it becomes an iterative work, which gets increasingly more ridiculous in the boy's imagination, until comes home and tells the non-fabulist version of plain old horse and wagon to his father.

It’s a book about creativity and storytelling. How to see something simple and imagine the possibilities. It’s about the power of the imagination. The same power that Charles Perrault used when he had the fairy god-mother turn a pumpkin into a stagecoach, and the lizards into footmen.

There is a logic at work as well. For example, he first replaces the horse with a zebra, before reconsidering replacing the wagon with a gold and blue chariot, before realizing that a zebra would be too small for a chariot, but a red reindeer would be a better choice, but a reindeer should really be pulling a sled.

However, a reindeer pulling a sleigh is too obvious, but a huge blue elephant pulling one is not.

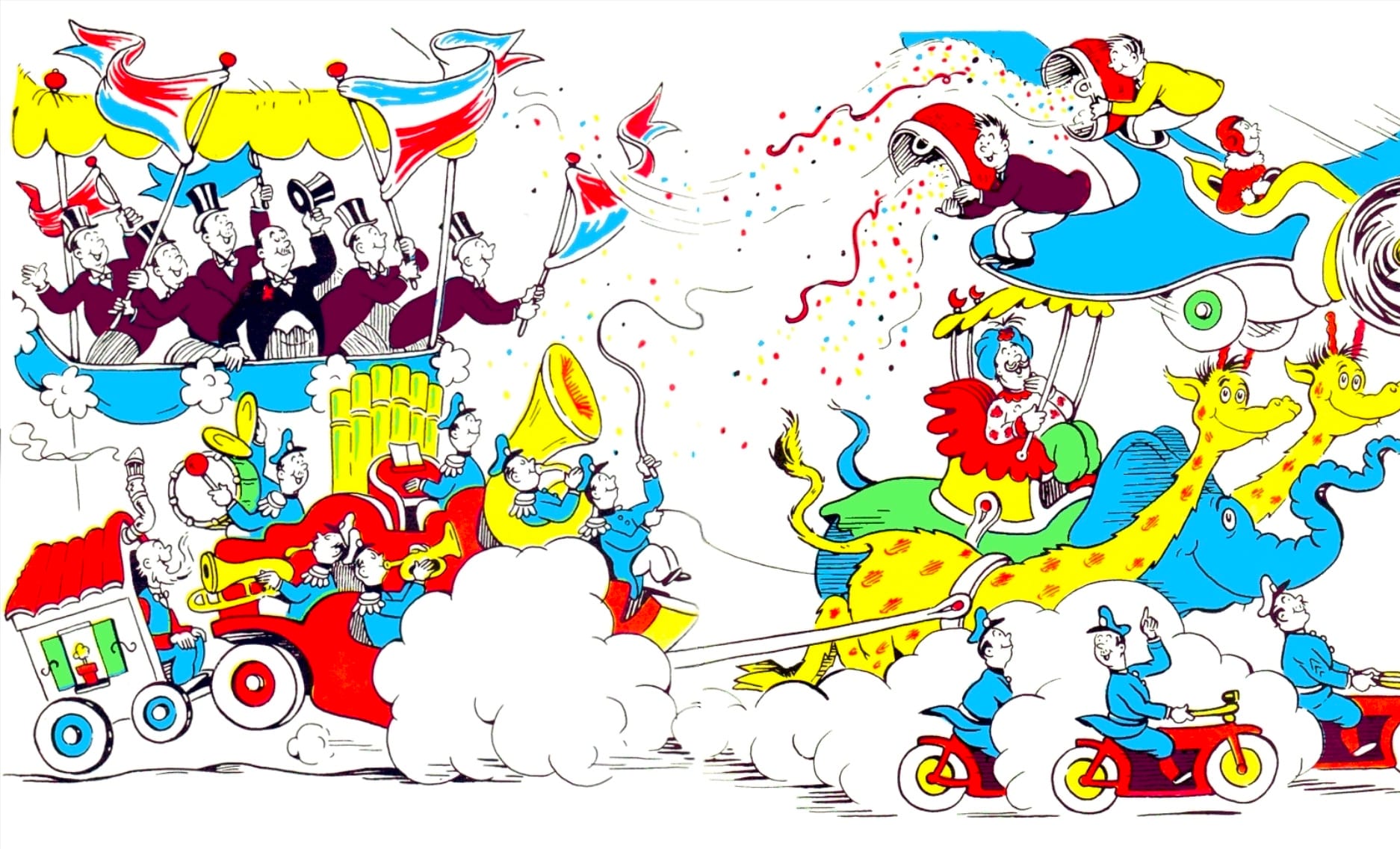

And so it continues in an absurdist fashion with this as the penultimate iteration:

The final iteration includes an illustration which caused his estate to stop publishing the book in 2021.

Reading #2 - You really can't imagine what happens next.

Dr. Seuss began work on Mulberry Street after returning from a trip to Europe in 1936. While he credits the cadence of the poem to the ship's engine, scholars connect the imagery with what he actually observed happening in Europe at that time, with the rise of Nazism.

In this reading, it's not quite clear what the moral is, because Marco doesn't tell his father his creative story. A possible understanding is that there are many stages between the horse and buggy of the first page and the sheer pandemonium of the final one. No one can look at a horse and buggy and jump right to the end. Everything seems logical, until it isn't.

Seuss' following books took a much more definitive stand against fascism, and he spent the war drawing political cartoons, which further emboldened him for his postwar work, with the environmentally conscious The Lorax being published in 1971.

Imperfect Man Writes Children's Books

There will always be critics, like an English teacher in the mid-1960s who felt like Dr. Seuss was resting on his laurels and wasn't really impressed by Hop on Pop (1963).

But there are valid criticism too. There are cartoons he created in his 20s which featured racist tropes, and even early during the war which were anti-Japanese. He actively was against the racism and anti-semitism of the late 1930s and early 1940s.

By the end of the war, he actively tried to undo some of the harm with regard to his depiction of the Japanese and Japanese Americans.

It reminded me of Albert Einstein during the war with his advocacy of The Manhattan Project and after the war with the founding of the Emergency Committee of Atomic Scientists, aiming to "harness the atom for the benefit of mankind, and not for humanity's destruction."

When The Unexpected Happens

In Oh, The Places You'll Go (1990), the octogenarian Dr. Seuss wrote honest advice, to generations of people raised on his books, taught to use their imagination at every turn.

Wherever you fly, you'll be best of the best.

Wherever you go, you will top all the rest.

Except when you don't.

Because, sometimes, you won't.

I'm sorry to say so

but, sadly, it's true

that Bang-ups

and Hang-ups

can happen to you.

You can get all hung up

in a prickle-ly perch.

And your gang will fly on.

You'll be left in a Lurch.

You'll come down from the Lurch

with an unpleasant bump.

And the chances are, then,

that you'll be in a Slump.

And when you're in a Slump,

you're not in for much fun.

Un-slumping yourself

is not easily done.

His ultimate advice is simple:

Step with care and great tact

and remember that Life's

a Great Balancing Act.

Just never forget to be dexterous and deft.

And never mix up your right foot with your left.

More questions than answers

First of all, was this final book inspired by his early studies in Milton's Paradise Lost?

I'm more confused about Dr. Seuss now than when I began researching his works, and that's probably a good thing. I've started working out a framework for his different uses of color, as both hues and rhymes, but it's too early to really know anything yet.

My notes are marked with similarities between Dr. Seuss and as wide a range of people from Charles Perrault, Jacob Grimm, and L. Frank Baum to Albert Einstein, George Orwell, and Mister Rogers to Jim Henson, Andy Warhol, and Roy Lichtenstein.

Advice for the New Year

I've written about curiosity, wonderment, and imagination, and I've always felt as if those were the lessons that Dr. Seuss championed.

And then I try to imagine, what would have happened if he hadn't sat next to Helen during a lecture, or not been hired by Flit, or faced with all the rejection for his manuscript, never published Mulberry Street. What if he never became a political cartoonist for PM during the war?

What if he had never been challenged to write a book using words from a list of 379 basic vocabulary words, which led to The Cat in the Hat and the Beginner Books imprint? At the very least, the Berenstain Bears wouldn't exist.

What would that world look like today?

In the 1940s, a similarly named Dr. Theodore Woodward taught his interns "When you hear hoofbeats behind you, don't expect to see a zebra."

In the new year, ignore that advice. Instead, we ought to remember to look at a horse and imagine a yellow- and black-striped zebra. I mean, I'm not quite sure how that would help anything, but it doesn't hurt to try.

Doctor's orders.